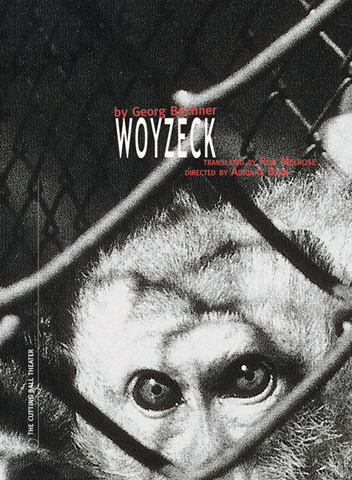

Woyzeck

by Georg Büchner

in a new translation by Rob Melrose

directed by Adriana Baer

March 15 through April 7, Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays 8pm

Student/Senior: $20

Adults: $25

"Under-30-Thursdays": $15 Under 30 with ID

Based on the most sensational criminal case of its time, Woyzeck chronicles the breakdown of a young soldier's mind. Used in medical experiments, trampled down by his superiors, Friedrich Johann Franz Woyzeck clings to the one thing that keeps him human.

Special Thanks: Matt Cullen, Joe Lauinger, EXIT Theater, Jonathan Stepakoff, Raoul Stepakoff, & Z-Space

This performance runs one hour and fifteen minutes with no intermission.

Adriana Baer – Director

Melpomene Katakalos – Set Design

Carlos Aguilar – Associate Set Design, Props Design

Raquel Barreto -Costume Design

Tavissa Granger – Assistant Costume Design

Rob Melrose – Lighting Design

Cliff Caruthers – Sound and Music Design

Dave Maier Fight – Choreography

Lucia Scheckner – Dramaturg

Kelli Jew – Associate Producer

Robert McPhee – Stage Manager

Viqui Peralta – Assistant Stage Manager

Ari Poppers – Technical Director and Master Electrician

Michael Podolin – Lighting Crew

Debra Singer – Graphic Design

Krystal Seli – Box Office

Cast:

(Alphabetical)

Felicia Benefield – Barker's Wife, Kathy, Child

Drea Bernardi – Marie

Chad Deverman – Woyzeck

Rebecca Martin – Horse, Margaret, Little Marie

Ryan Oden – Doctor

Matthew Purdon – Drum Major, Merchant

John Russell – Under Officer, Innkeeper, Child

Bill Selig – Ape, Andres

David Sinaiko – Carnival Barker, Captain

Woyzeck is the Open Wound

by Lucia Scheckner, dramaturg

“A text many times raped by the theater, a text that happened to a twenty-three-year-old whose eyelids were cut off at his birth by The Weird Sisters, a text blasted by the fever to orthographic splinters, a structure as it might be created when lead is smelted at New Year’s Eve since the hand is trembling with anticipation of the future…”

— Heiner Müller

Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck examines the nature of man as a social animal and in a remarkably prophetic and brief text manages to embody the inconsequence of existence and Kafkaesque landscape of a humanity doomed to wander from one holocaust to the next. The play captures the twentieth century experience.

Büchner died of typhus in 1837 at the age of twenty-three, leaving behind a small but exceptional trove of dramatic literature: Danton’s Death (1835); Leonce and Lena (1836); and Woyzeck (1836). He also published one novella, Lenz (1836), and a prominent revolutionary political pamphlet, The Hessian Messenger (1835). In the pamphlet, Büchner encourages the peasantry to rise up against the oppressive Hessian government and expresses his disgust with the ruling class’ appropriation of Christianity to oppress individual freedom. Büchner’s reputation as a political activist and rising scholar became increasingly widespread as a result, but his talent as a playwright remained unnoticed. His own generation was not ready for his startling representations of violence and dehumanization, but such themes resonated deeply with twentieth century audiences. Büchner’s writing has since been an ongoing source of influence throughout modern theater.

Büchner anticipated almost all of the major artistic movements of the twentieth century: Naturalism; German Expressionism; Surrealism; Dadaism; and Brecht’s dialectical theater, among many others. Both his focus on the working class and his thematically and structurally unresolved writing – which resists a single interpretation – represent turning points in the development of modern art. Büchner’s anti-classical dramaturgy gives new power to readers, encouraging them to be authors – to give meaning to a particular work of art – by applying their own perspective. Among his plays, Woyzeck best embodies these innovations. It continues to have an impact on and stir controversy in audiences, an amazing achievement for a play that the author never completed.

After Büchner’s death, a mess of illegible manuscripts and drafts of Woyzeck – made up of twenty-seven self-contained scenes – were found. Later, a letter written by Büchner to his girlfriend was also discovered. In it the playwright claims to be days away from completing his three plays, one of which was Woyzeck. Contemporary scholars argue that the letter proves that the sequence of scenes in Büchner’s final draft is likely to represent the author’s ultimate intention. Yet, as it is unauthorized, the incompleteness of the text has charged generations of theater artists with the task of composing their own narrative.

Woyzeck was first published by Karl Emil Franzos in 1879 after significant revisions and was first performed in 1913 in Munich. It was then adapted into an opera, Wozzeck, by Alan Berg between 1914 and 1922, first performed in 1925. Berg’s rendition contributed to a greater understanding and appreciation of Woyzeck’s form and the liberties its structure affords. In particular, since the lack of logical continuity from one scene to the next prevents the play from having a coherent comprehensive history, directors are able to envision a social and historical totality of their own choosing, making the play a uniquely powerful political tool.

Tackling the unfinished Woyzeck has become a tradition, almost a rite of passage, among emerging theater artists. This perhaps explains why Woyzeck is one the most frequently produced plays in the U.S. and throughout Europe.

Büchner’s politics, which expanded while he studied philosophy and science in Giessen, are embroiled in Woyzeck. Its central themes – violence, animal nature, sexuality, insanity, poverty, and suffering – reflect the young scholar’s commitment to examining the raw nature of life both in academic and literary spheres. The central narrative of Woyzeck is of particular interest because it draws upon the actual events of a soldier, Johann Christian Woyzeck, who was executed in 1821 after murdering his lover in a jealous rage. The trial attracted a great deal of excitement because of inquiries made concerning the soldier’s mental stability.

In Büchner’s Woyzeck, the world is a hallucinatory nightmare, in which people are denied full humanity. At the center of this exploitation is a poor soldier who becomes so overwhelmed by divergent social demands that his experience of reality slowly erodes into insanity. Through the play’s episodic structure, which accumulates rather than unfolds, Büchner creates a rhythm of erratic fervor that reflects the process of Woyzeck’s mental deterioration. Büchner also makes an explicit connection between poverty and suffering. As Woyzeck says to the Captain, “I think, when we [poor people] come into heaven, they’ll make us help with the thunder.” If not for his lower-class status, Woyzeck wouldn’t have to participate in the physically abusive and unethical experiments carried out by the Doctor, nor would he be forced to endure the mental abuse of the Captain. Ultimately, the tormented Woyzeck submits to his untamed nature and lashes out against these injustices by tragically murdering his lover.

Büchner’s analysis of human suffering, however, is not based on class-structure alone. His portrait of the human animal suffering existential emptiness is rooted in an understanding that, as the German playwright, Heiner Müller, stated, history moves dialectically through tragedy after tragedy. Woyzeck is the open wound, says Müller, he is the archetype – like Christ and Hamlet – of the universal human experience of inevitable and senseless suffering.

Throughout his studies Büchner became preoccupied with the relationship between free will and determinism as well as human behavior and animal impulse. Theater scholar Richard Schechner observes, “The struggle in Woyzeck is not simply between classes, but between species.” Büchner came to believe that ultimately only physical laws are of real consequence. He was disillusioned by the idea of the automaton, as articulated in a letter he wrote to his girlfriend: “The individual is only foam on the wave; greatness is simply chance; the rule of genius is a puppet play, a ridiculous struggle against a pitiless law: to recognize it is the ultimate; to control it is impossible.” Haunted by a vision of human beings as mere slaves to uncontrollable external forces, Büchner’s writing concentrated on the bestiality of man. Within his canon Woyzeck demonstrates most directly the inability of human beings to escape animal urges, the resulting disintegration of human logic, and the destructive chaos that ensues.