Antigone’s Origins: Theatre in Ancient Greece

In the midst of producing a work of theatre, between the rehearsals, design meetings, production meetings and countless cups of coffee (or tea) it is easy to forget that the roots of theatre are easily over two thousand years old (maybe older). Theatre today is still strongly influenced by the theatre of ancient Greece, not only in modern adaptations of Greek plays but also in the building blocks of any fledging production.

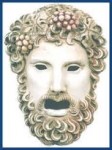

Ancient Greek theatre evolved from religious rites or ceremonies to honor and celebrate the Greek God Dionysus (God of wine and fertility). The dithyramb (an ancient Greek ceremonial hymn) was an essential part of these ceremonies. Dithyrambs were often sung or performed by a group, and they paved the way for what would become Greek theatre.

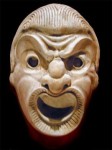

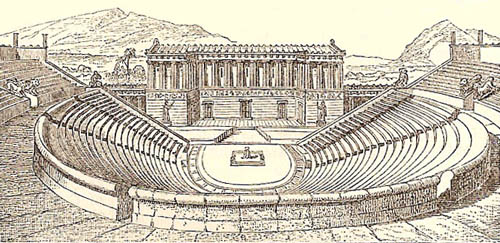

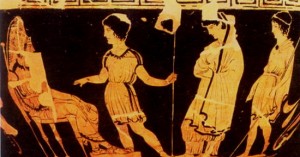

The plays of ancient Greece were performed in outdoor amphitheaters that eventually accommodated up to fourteen thousand spectators. The earlier theatres usually consisted of a flat, circular dancing space (orchestra) at the foot of a hill, which would be associated with a small temple of Dionysus. The hill then would provide a natural seating area for the spectators (theatron). The Greeks added scenic buildings (skene, pl. skenai) to the later theatres, which provided a space for the actors to enter and exit. Skenai also provided space to store props, change costumes, and paint sets. Even though these theatres were massive and could accommodate thousands, the acoustics allowed everyone seated in the audience to hear the performers. Both the actors and the chorus usually wore masks (which are known to be a significant element of worship of the god Dionysus). For the comedic plays, the masks were modeled often on known individuals such as politicians, playwrights and other notable figures. They were also useful if actors had to play multiple parts. The masks, as well as the movement and speech of the actors, were large and exaggerated in order to reach the spectators in the very last row. For more information and pictures.

The plays can be categorized into three categories. Tragedy and comedy were the most prominent, but there was a third type of performance called satyr. This genre tended to be satirical and over the top – much like what we think of as burlesque or even vaudeville. The most well known ancient Greek playwrights are: Aeschylus (c. 525 – 456 B.C.), Sophocles (c. 496 – 406 B.C.), Euripides (c. 485-406 B.C.), Aristophanes (c. 450-385 B.C.) and Menander (c. 342-290 B.C.). It is important to note that most of what these playwrights wrote has been lost. What we know about ancient Greek theatre stems from the surviving plays. The texts themselves are incomplete in that there is no real way to know how the playwrights wanted the plays to be staged, or what the music was supposed to be, or what the dancing was supposed to look like. While we have archaeological information regarding the structures of the theatres themselves, and access to the ancient texts, we’ll never quite understand the theatrical aspects of the plays because of the fleeting nature of theatre.

Even though only a fraction of what must have been written survives today, countless modern adaptations have been made of Greek tragedies and comedies all over the world. In fact, every contemporary performance of a Greek play could be considered an adaptation because it had to be translated from the ancient Greek language of the original text, and any music and dance indicated in the script had to be interpreted. Some argue that this barrier actually makes it easier to contemporize the material. Being unhindered by the theatrical conventions of ancient Greece allows for different interpretations. The adaptations of the play Antigone by Sophocles alone are in the thousands, from opera to cinema to Brecht; from Europe to Latin America to Asia.

Antigone is a tragedy by Sophocles and is the third play in the Oedipus Cycle. In the play, Antigone goes against the orders of her uncle Creon, King of Thebes, by burying her brother Polynices. The character Antigone is interpreted differently depending on the adaptation. She is often a political figure, standing up to the government. She can be a philosophical figure, inciting debates such as conscience versus law. Antigone often embodies familial ties. She is a feminist as she does not conform to the gender norms of the time. She can be seen as strong-willed and selfish. There is no single correct interpretation of Antigone. She is all of these things, or none of them. It is up to current theatre makers and theatre goers to decide.

By Carissa Ibert

July 22, 2014